Finding a solution to plastic pollution

When plastic was first developed just over a century ago, it was hailed as a wonder material; something that would transform all our lives for the better and reduce our need to cut down ever increasing numbers of trees.

Instead, with hindsight and experience, history will record a different legacy for plastic; one centered on its hugely damaging and long-lasting impact on our planet and on our natural environment.

The statistics are little short of shocking.

- Half of all plastics ever manufactured have been made in the last 15 years.

- In 2019, the production of plastics totaled around 368 million metric tons worldwide.[1]

- In just one week, from bottled water alone, the US produces enough bottles to circle the planet five times.[2]

- A million plastic bottles are bought around the world every minute.[3]

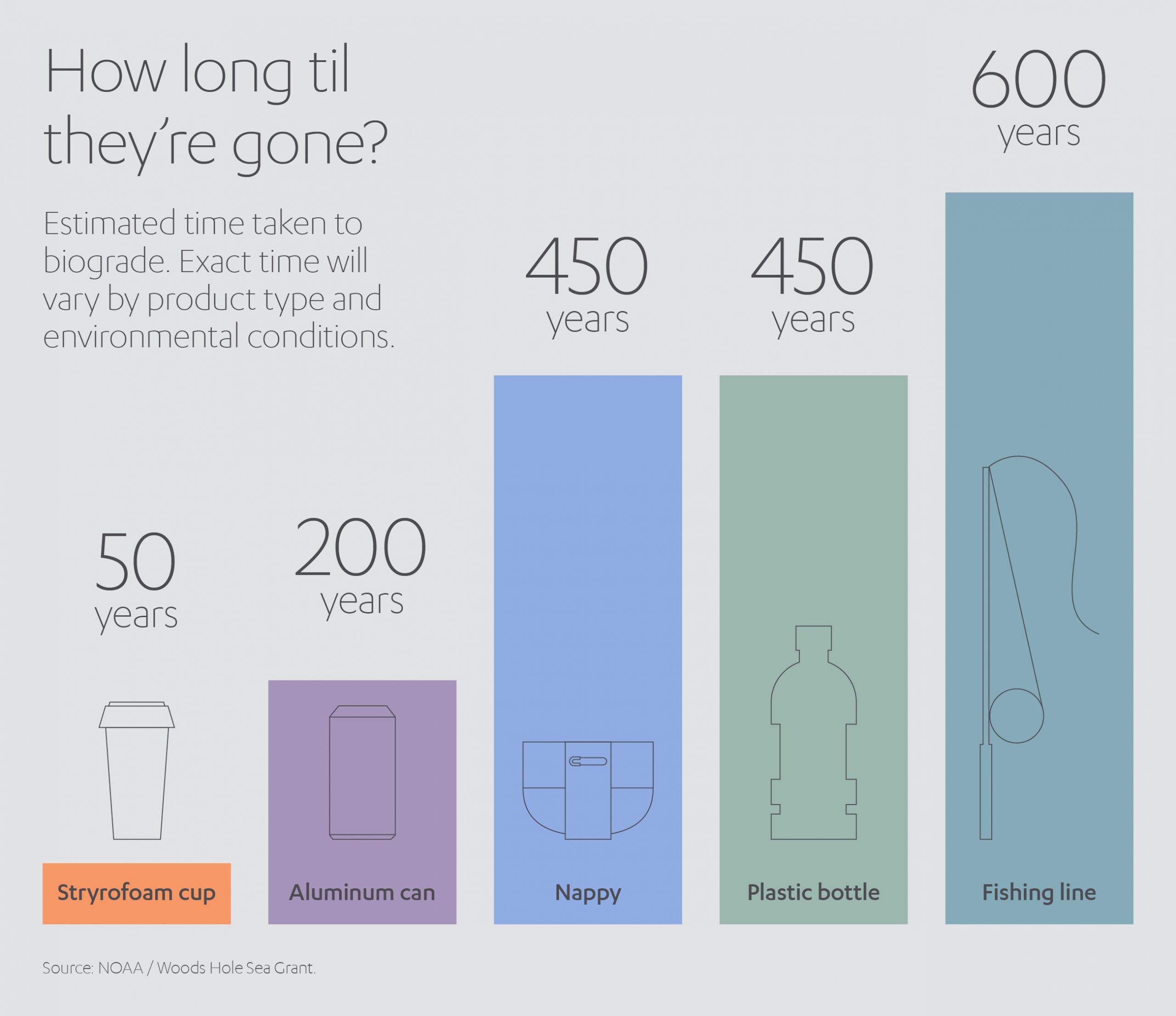

- Some plastics can take up to a thousand years to decompose.

- 73% of beach litter worldwide is plastic. [4]

- In as little as 30 years’ time there could be more plastic in the ocean, by weight, than fish.[5]

Plastic is ubiquitous. Plastic is enduring. However, so too is human ingenuity. And that could be our savior. As we step into the age of technology, still wedded to the age of plastic, it is our capacity for innovation that could rescue us from this self-inflicted plague.

We are often told that plastic is indispensable. That it takes a lifetime or longer to break down. That there is no economically viable alternative. But are these conventional wisdoms as unambiguous as they appear, or is our future relationship with plastic yet to be determined?

To comprehend the opportunities which lie ahead, we must first understand the nature of the challenge before us.

Plastic facts are all too easy to swallow

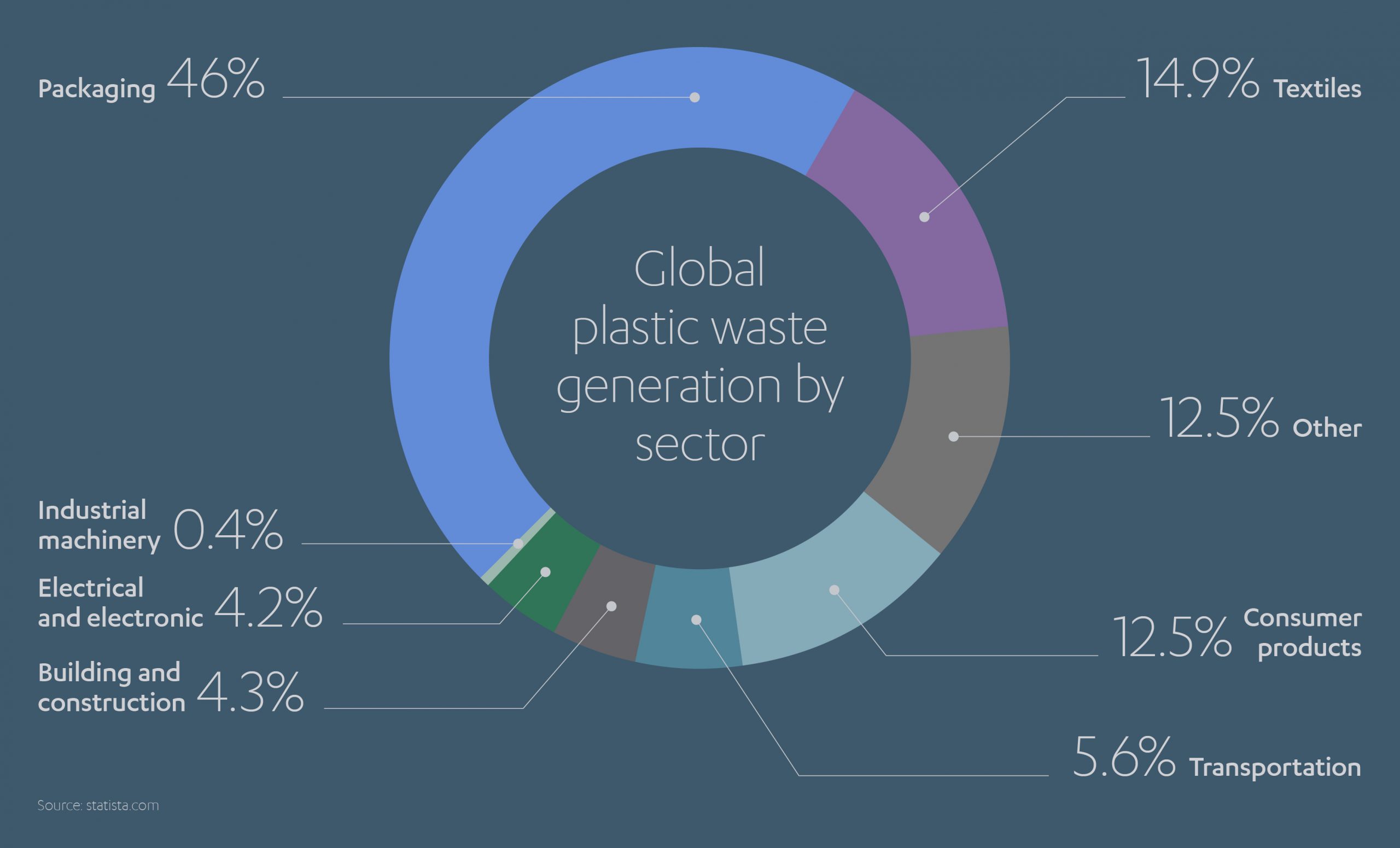

While many consumer industries have taken steps to address their plastic waste, the problem is far too big to be solved in isolation.

Plastics envelop our daily lives, and culpability extends to some of the world’s biggest brands.

A study by environmental advocacy group Break Free From Plastic found Coca-Cola, Pepsi and Nestlé to be the top three global plastic ‘polluters’ for the third year in a row.[6]

Earlier this year those three brands, plus Unilever, were blamed as the source producer for 500,000 tons of our society’s plastic pollution annually in six developing countries.[7]

To their credit, all four of these global corporates are taking steps to reduce their contribution to plastic pollution. Coca Cola, for example, has pledged to increase the amount of recycled content in plastic bottles to 50% by 2030, while Nestle has promised to make all its plastic packaging 100% recyclable or reusable by 2025. But the problem is far too big for even the biggest companies to tackle alone.

According to the UN, plastic debris causes the death of approximately a million seabirds and 100,000 marine animals annually.[8]

And as we are becoming increasingly aware, it’s not just harmful to animal life, but to human life, too.

Microplastics, pieces less than 5mm in length, have been working their way into the food chain with surprising ease. Some estimates suggest we each consume an average of 21 grams of plastic per month – enough to half-fill a rice bowl.[9]

No one even pretends this is good news. So, shouldn’t we be doing something about reducing our reliance on plastics?

Thinking outside the (plastic) box

Probe beneath the surface and we find that eradicating plastics from our lives is easier said than done. Some of the alternatives so far proposed come with drawbacks of their own.

So-called biodegradable bottles, for instance, often derived from plants, require an environment of suitably high heat and moisture levels to allow microbes to break down the polymer. Such bottles also frequently contain linings or chemicals resistant to natural degradation.[10]

Attempts to solve the single-use plastic bag issue are laudable, particularly with more than a trillion produced annually. Biodegradable bags appeared briefly to offer a solution, but celebrations proved premature. Oxo-degradable bags (that is, bags which can decompose naturally in fresh air) were hailed as a breakthrough, even prompting Saudi Arabia in 2017 to outlaw all single-use plastic bags made from non-oxo material. However, later research showed that rather than ‘disappear’, oxo-bags merely broke down into those dreaded microplastics and continued their journey around the ecosystem.[11] Plus, they often end their days in landfills where they release greenhouse gases into the environment.[12]

Paper bags come laden with problems too, inevitably being ultimately, if albeit indirectly, linked to deforestation.

Bamboo straws seem the ideal remedy to the 170 million plastic straws Americans use daily, however most bamboo is grown in China, so entails a considerable carbon footprint in transporting it around the world.

Clothes and shoes manufactured with recycled plastic appear noble, but merely give plastics a temporary home on the backs or feet of shoppers, before ultimately returning them to the ecosystem.

Seaweed, which has the benefit of growing up to three meters a day, produces a sturdy material called agar which biodegrades in no more than six weeks; however, creating enough seaweed farms to counteract the world’s predilection for plastic would chemically alter the composition of the world’s oceans, with unknown consequences.[13]

Clearly, the issue is a complex one and a magic bullet solution is so far proving elusive. Still, research continues into genuine alternatives to plastic which may provide more long-lasting environmental benefits: milk protein to make insulation and furniture foam; chicken feathers for water-resistant thermoplastics; liquid wood from pulp-based lignin for product packaging; and PCL, PHA and PLA polyesters, compounds which are either biodegradable or created with natural ingredients, such as wheat and sugarcane.

Until these concepts come to fruition and find widespread adoption, it is our waterways that are bearing the brunt of ‘planet plastic’.

Floating ideas for a deep problem

Photo Credit: © Noel Guevara / Greenpeace via EPA

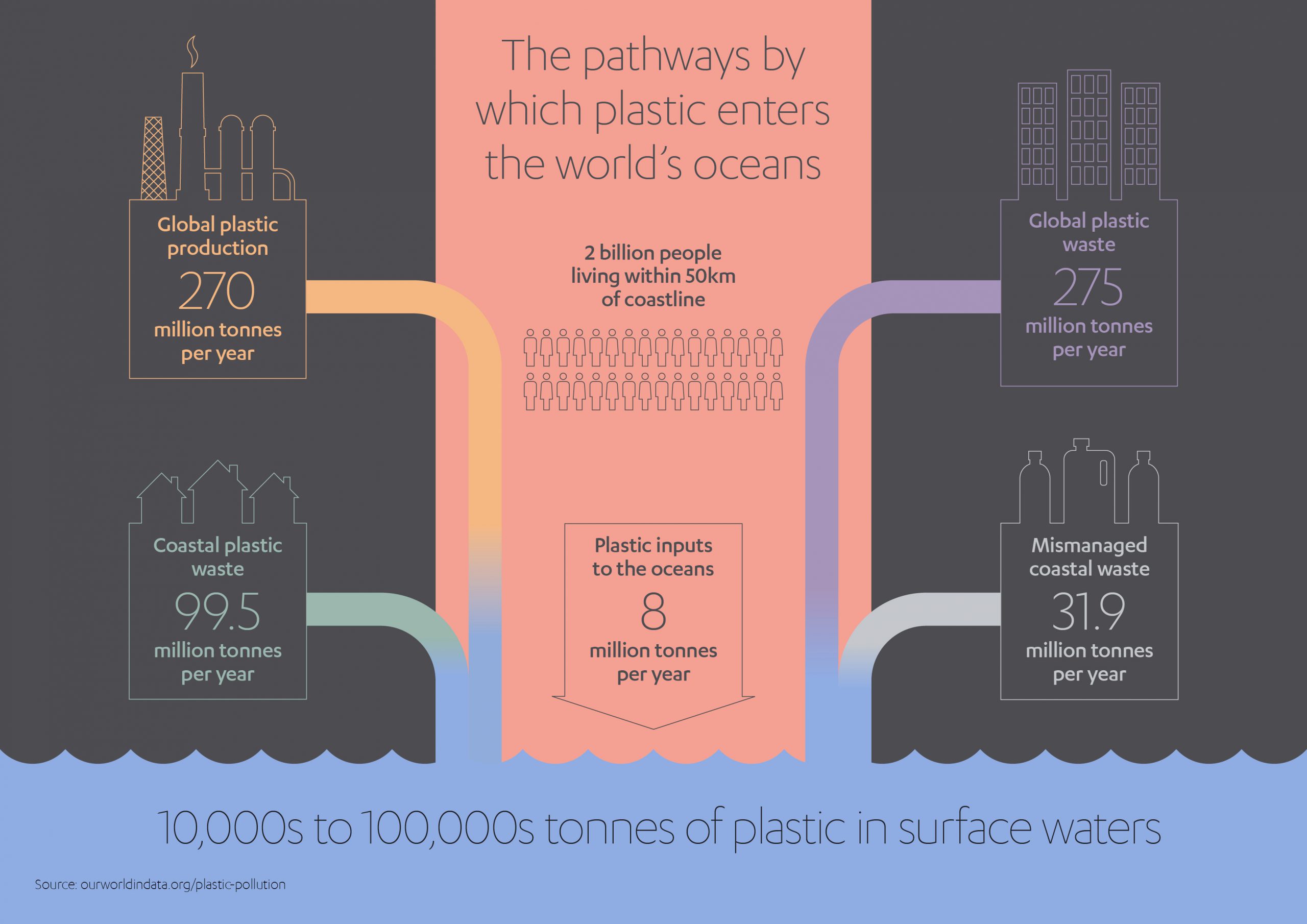

It will come as little surprise to anyone living or holidaying near the coast that most of the world’s surplus plastic ends up in our oceans.

Rather like icebergs, visible plastics on the ocean surface represent merely the tip of an altogether more sinister presence. Just 3% of ocean plastics are free-floating.[14] The rest, according to the World Resources Institute (WRI), “sinks to the ocean floor, stays suspended in the water column, or gets deposited out of the ocean in remote places, making clean-up difficult”.[15]

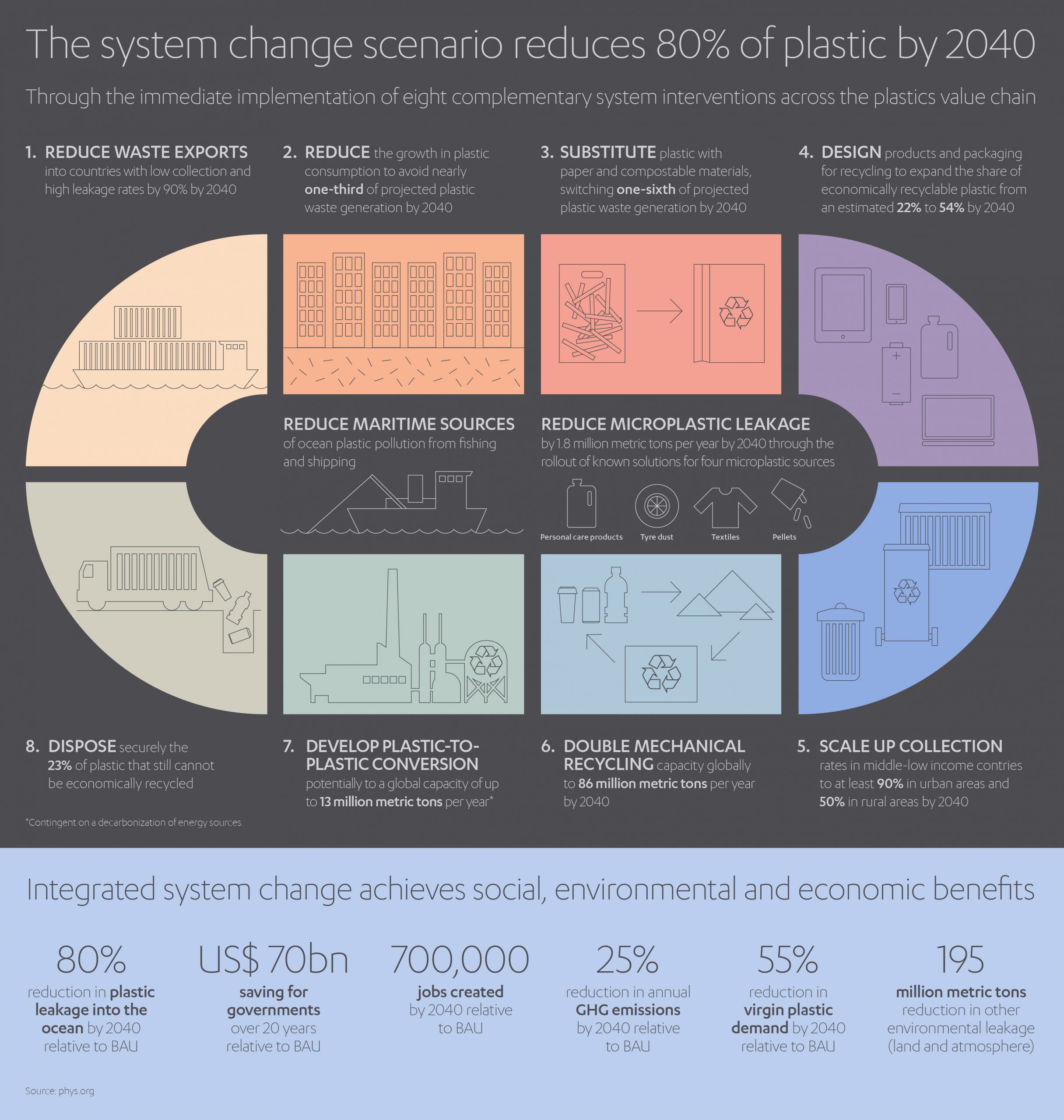

The WRI recommends a multi-pronged approach to fixing – or at least, beginning to tackle – the issue.

- Improving wastewater management for the half of the world’s population lacking basic waste disposal facilities, to cut the number of plastics present in untreated water.

- Upgrading stormwater management via drain filtration and river mouth trash collection, to prevent both macro and microplastics from entering the water cycle.

- Banning ‘hard to manage’ substances such as expanded polystyrene, often used in packaging, and funding research into viable alternatives.

- Introducing voluntary industry standards to reduce the production of fossil-fuel-based plastics.

- Establishing clean water facilities for all communities, notably the one-in-three people around the world who lack potable supplies, thus reducing the need for bottled water globally.

It is human nature that the most effective strategies will bring benefits both environmental and economic.

In East Java, Indonesia, for example, a public-private partnership in 2019 led to a new waste management system for a community of almost 50,000 people, collecting 3,000 tons of waste while simultaneously creating 80 jobs.[16]

This project offers a mere taste of the kind of initiatives that can begin to put a real dent in the plastic conundrum. Everyone, from individuals to the largest corporates, can play their part in reducing the consumption of plastics. It is a responsibility we take seriously at Abdul Latif Jameel.

This project offers a mere taste of the kind of initiatives that can begin to put a real dent in the plastic conundrum. Everyone, from individuals to the largest corporates, can play their part in reducing the consumption of plastics. It is a responsibility we take seriously at Abdul Latif Jameel.

Almar Water Solutions, for example, part of Abdul Latif Jameel Energy, has introduced an initiative to reduce the use of plastic bottles in five group businesses. By replacing plastic bottles in offices with water jugs and re-usable glass and metal bottles, it saved around 25,000 kg of plastic and cut costs by approximately US$ 120,000 per year.

Incentivizing a plastic pollution revolution

Politically, governments are beginning to apply pressure to the plastics industry by introducing new regulations to constrain their less desirable impulses.

The EU, for instance, introduced strict new rules on single use plastics in 2019. Among other measures, the Single Use Plastic Directive banned products for which practical alternatives already exist, such as cotton bud sticks and straws. It also introduced clean-up levies for producers of common pollutants, such as cigarette filters and fishing gear, set a 90% plastic bottle collection goal by 2029, and a target of at least 30% recycled plastic in all plastic bottles by 2030.

In Kenya, manufacturers and suppliers have since 2017 faced fines in the tens of thousands of dollars for using plastic bags, prompting supermarket chains to start offering customers cloth bags as alternatives.[17]

Likewise, laws introduced to the UK in 2015 compelling shops to charge for plastic bags saw demand for disposable carriers drop by 80%, equivalent to 9 billion bags (and counting) to date.[18]

The chemicals industry, responsible for producing the majority of the world’s plastics, isn’t standing idly by and waiting for its operations to be regulated out of existence. Instead, it is seizing momentum in the private sector to discover new and profitable ventures based around recycling – unlocking profits up to US$ 55 billion annually by 2030, according to estimates.[19]

Currently only approximately 16% of plastics worldwide are reprocessed. The remainder, destined for landfill or incineration, can be considered true waste because it will never release its potential value.

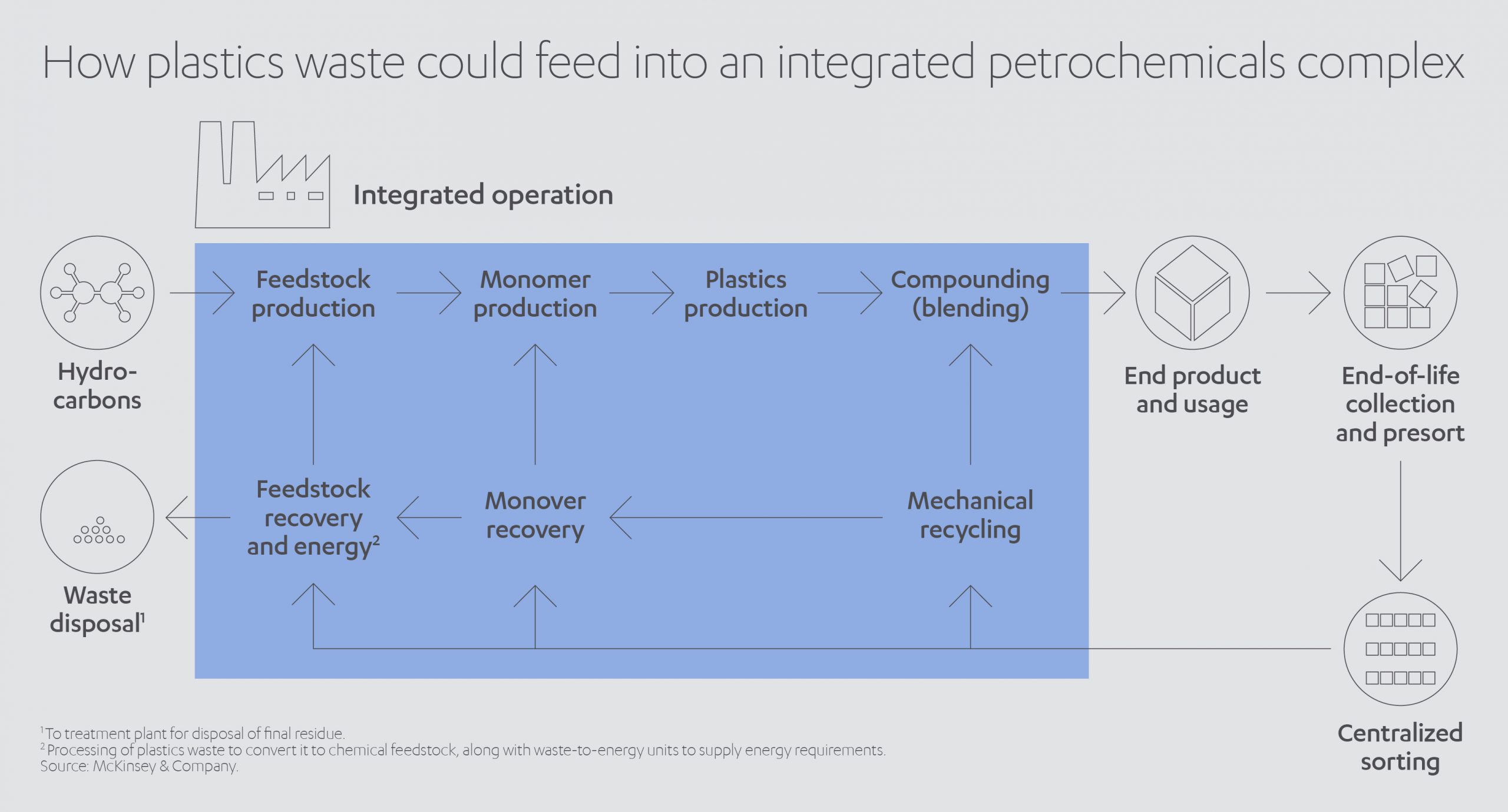

Reuse encompasses three areas:

- mechanical recycling, i.e. processing plastics such as polyethylene terephthalate (PET) back to resin pellets while leaving the polymer chain intact

- chemical recycling, i.e. breaking down the plastics to their monomers, suitable for polyesters and polyamides

- processing back to basic fuel (feedstock), i.e. using catalytic or thermal processing to break down polymer chains to hydrocarbon fractions

The industry is presently researching ways to optimize these processes.

In mechanical recycling, for example, one key challenge involves preserving the resin quality to avert deterioration during recycling.

In feedstock production, meanwhile, emerging technologies such as pyrolysis could enable poor quality mixed plastics such as flexible packaging (which current machines cannot accommodate) to be reprocessed.

Global consultancy McKinsey believes by 2030 the amount of plastic being recycled could increase fivefold to 220 million metric tons per year.[20] Given the precedent set by the aluminum and paper industries, where producers evolved to make recycling a key part of their business model, McKinsey sees vast scope for the chemicals industry to monetize its products throughout their (lengthy) lifespans.

Some chemical companies are already laying the groundwork. Borealis (Austria) and LyondellBasell (Netherlands), to name only two of many, have purchased polymer-recycling companies in Europe. SABIC (Saudi Arabia) is developing next-generation pyrolysis and chemical recycling methods to enable higher margins for reprocessing plastic waste.

McKinsey envisages a future of ‘fully integrated’ processing plants able to accept used plastics alongside traditional feedstocks – with waste-based fuels becoming competitive with oil-based fuels at US$ 65 a barrel.

Clearly the market is changing fast and technology is racing to keep pace. As we shall see, unpredictable events such as Covid-19 can provide a spur to other business opportunities.

Navigating a plastic pandemic

The coronavirus pandemic has seen the world’s appetite for personal protective equipment (PPE) skyrocket. Much of it plastic; much of it single-use.

In China, some 116 million facemasks were being produced daily by February, compared to 20 million prior to the outbreak. Global facemask sales are expected to increase to US$ 116 billion in 2020 compared to US$ 800 million in 2019.[21] In Thailand, plastic waste hit 6,300 tons daily in May, up from 5,500 tons pre-pandemic.

The knock-on costs of the plastic surge could hit US$ 40 billion across industries such as tourism, fishing and transport.

The global swing to online shopping during COVID-19’s malign reign has led to soaraway levels of plastic packaging. In Singapore alone, households were estimated to have generated 1,134 tons of packaging from food deliveries during its eight-week summer lockdown.

Forward-thinking organizations across emerging markets are waiting to pounce on these unexpected opportunities.

Business analysis and research firm Oxford Business Group notes that:

- in Ghana, authorities distributed facemasks made using recycled water bottles and ice cream sachets;

- in Tanzania, paper waste processors at Zaidi Recyclers shifted their focus to producing facemasks made from secondhand plastic bottles;

- and in Thailand, design company Qualy used more than 1.3 tons of old fishing nets to make face shields and disinfectant bottles for buyers across Europe and Asia[22].

These nascent initiatives may feel like drops in the (heavily polluted) ocean, but collectively demonstrate how the collision of innovation with circumstance can offer hope for even the most perplexing of dilemmas.

Investing in a plastic-free future

If the greater good is served – a world of less plastic, fewer chemicals and cleaner oceans – there is nothing immoral in profiting from resolving the world’s plastic predicament. Indeed, it may prove the only way of turning a movement into a revolution.

We have observed how government intervention can make tangible differences at ground level by reducing the amount of plastics we consume. And we have seen how private companies, whether chemical giants or innovative startups, are helping transform the plastics already in existence into useful commodities with ongoing roles to play – bestowing upon them a kinder fate than ending their days as harmful flotsam and jetsam.

Here we have a living example of a market opportunity, one which can inspire private investment from socially-conscious organizations like Abdul Latif Jameel to further strengthen their green investment portfolios and improve the infrastructure of life for all.

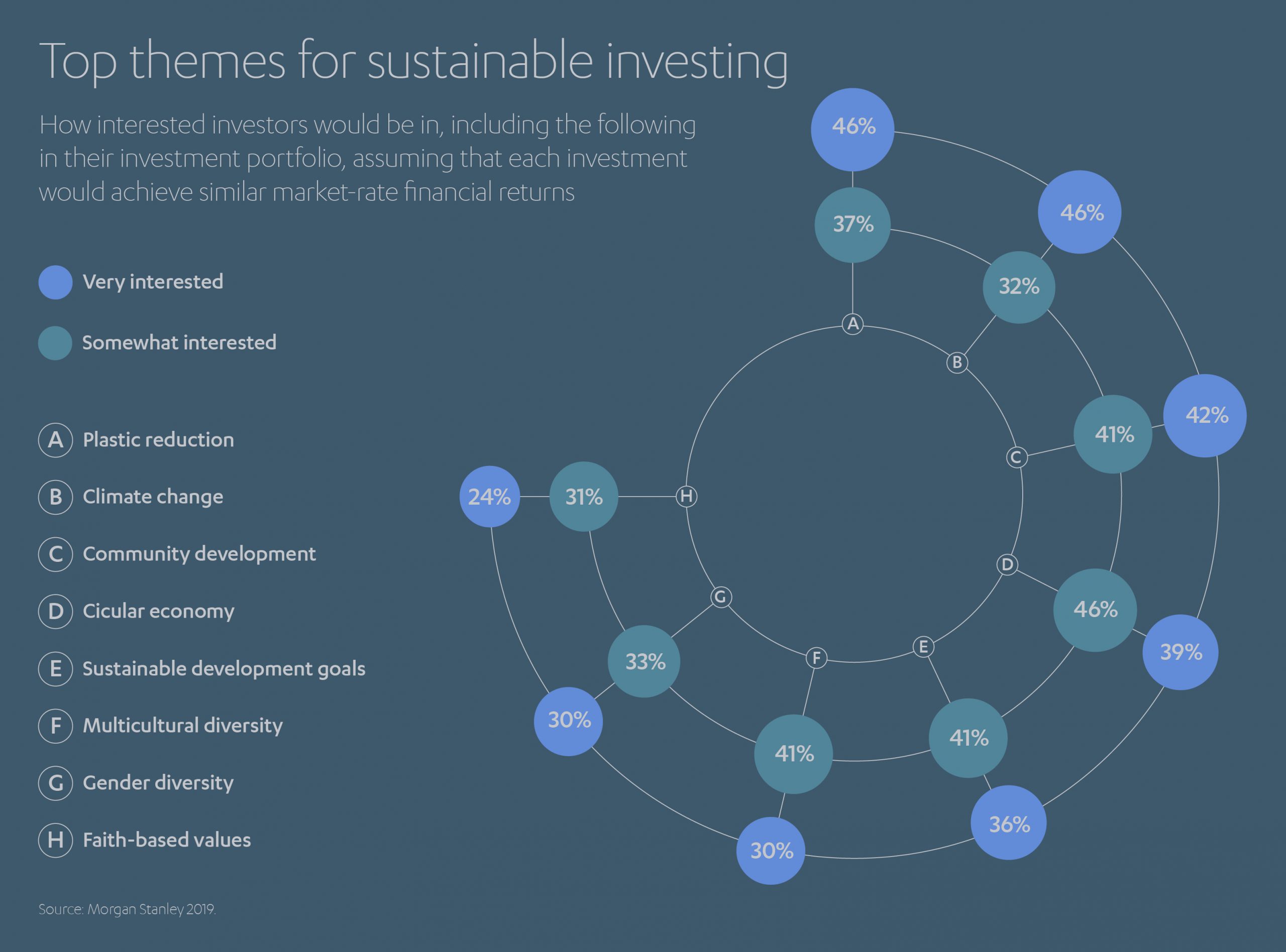

Indeed, channeling money into ethical causes is a growing trend. The concept of ESG (Environmental, Social and Governance) investing has risen in prominence alongside growing global awareness of issues such as the climate emergency. With investors increasingly wondering what their cash can achieve as well as what it can earn, key issues such as plastics will benefit.

ESG funds are tipped to grow threefold by 2025, their share of the European fund sector alone rising from 15% to 57% in that timeframe. Driven by this enthusiasm, sustainable investment products across the continent are forecast to hit €7.6 trillion over the next five years.[23]

Plastics could find themselves at the forefront of this ESG wave, with one survey suggesting more than four-in-five potential investors are motivated to plow funds into commercial plastic-reduction initiatives. The survey notes that such investors are seeking “a double bottom line: an ROI on their money, while also making the world a more sustainable place”.[24]

Via ESG funding, the private sector is demonstrating its capacity for a more pre-emptive approach to ethical investment than governments. And it is truly forward-thinking businesses -and there are many, such as Abdul Latif Jameel – that are showcasing private capital’s potential for ‘doing the right thing’.

Of course, philanthropic investment has a critical place, but this tends to be more upstream, in novel and innovative research – not all of which will become viable.

However, it is the power of private capital flows that can really drive the business behavior of today to make substantive and meaningful sustainable differences right now.

As part of our own due diligence, we evaluate the sustainability of all our investment strategies, particularly in private markets. Not just in terms of environmental factors, but also whether the business model itself is sustainable. It is highly unlikely we would invest in a carbon dependent energy fund, for example. Like any investor, our mandate is to generate an acceptable financial return – and we believe sustainability in climate and the environment are critical factors in achieving this, hence our investments in areas such as renewable energy, electric vehicles and water technologies. This latter category including desalination water and wastewater treatment and reuse and also in aquaculture.

Of course, another powerful catalyst for a less plastic-reliant world may come from a gradual – but rapidly accelerating – and global shift in mindset.

We might arrive at a cultural ‘moment’, much sooner than we think, when buying a drink in a plastic bottle or food packaged in a plastic tray is done only with great reluctance and perhaps rightfully, given that we are all well aware of the consequences, some sense of personal guilt.

It is only by changing our priorities – societal, commercial and of course personal – opening our eyes to the true costs, and affordably commercializing new innovations, that a long-term solution to plastic pollution can ever be achieved.

At Abdul Latif Jameel, I am truly hopeful that this moment is within our reach, and that by working together, we can build a sustainable, plastic-free future for our society and our planet.

[1] https://www.statista.com/statistics/282732/global-production-of-plastics-since-1950/

[2] https://www.waterdocs.ca/water-talk/2018/4/7/facts-about-bottled-water

[3] https://www.waterdocs.ca/water-talk/2018/4/7/facts-about-bottled-water

[4] https://www.waterdocs.ca/water-talk/2018/4/7/facts-about-bottled-water

[5] https://www.theguardian.com/business/2016/jan/19/more-plastic-than-fish-in-the-sea-by-2050-warns-ellen-macarthur

[6] https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2020/dec/07/coca-cola-pepsi-and-nestle-named-top-plastic-polluters-for-third-year-in-a-row?

[7] https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2020/mar/31/report-reveals-massive-plastic-pollution-footprint-of-drinks-firms

[8] http://www.unesco.org/new/en/natural-sciences/ioc-oceans/focus-areas/rio-20-ocean/blueprint-for-the-future-we-want/marine-pollution/facts-and-figures-on-marine-pollution/

[9] https://graphics.reuters.com/ENVIRONMENT-PLASTIC/0100B4TF2MQ/index.html

[10] https://www.globalcitizen.org/en/content/plastic-alternatives-doing-harm/

[11] https://www.ellenmacarthurfoundation.org/assets/downloads/publications/NPEC-Hybrid_English_22-11-17_Digital.pdf

[12] https://www.thequint.com/news/environment/plastic-biodegradable-environment-reuse-recycle

[13] https://www.wired.co.uk/article/plastic-alternatives

[14] https://oceanpanel.org/blue-papers/leveraging-target-strategies-to-address-plastic-pollution-in-the-context

[15] https://www.wri.org/blog/2020/05/how-to-reduce-plastic-ocean-pollution

[16] https://www.wri.org/blog/2020/05/how-to-reduce-plastic-ocean-pollution

[17] https://uk.reuters.com/article/uk-kenya-plastic/kenya-imposes-worlds-toughest-law-against-plastic-bags-idUKKCN1B80PZ

[18] https://www.wri.org/blog/2020/05/how-to-reduce-plastic-ocean-pollution

[19] https://www.mckinsey.com/industries/chemicals/our-insights/no-time-to-waste-what-plastics-recycling-could-offer

[20] https://www.mckinsey.com/industries/chemicals/our-insights/no-time-to-waste-what-plastics-recycling-could-offer

[21] https://oxfordbusinessgroup.com/news/can-covid-19-plastic-waste-problem-generate-business-opportunities?utm_source=Oxford%20Business%20Group&utm_medium=email&utm_campaign=11826503_Covid-19_Plastics_September%2016_EU&utm_content=EIA-recycling-16-Sept&dm_i=1P7V,71HDZ,S7I7K1,SENOP,1

[22] https://oxfordbusinessgroup.com/news/can-covid-19-plastic-waste-problem-generate-business-opportunities?utm_source=Oxford%20Business%20Group&utm_medium=email&utm_campaign=11826503_Covid-19_Plastics_September%2016_EU&utm_content=EIA-recycling-16-Sept&dm_i=1P7V,71HDZ,S7I7K1,SENOP,1

[23] https://www.ft.com/content/5cd6e923-81e0-4557-8cff-a02fb5e01d42

[24] https://www.visualcapitalist.com/five-drivers-behind-the-sustainable-investing-shift/

1x

1x

Added to press kit

Added to press kit